Key Takeaways

- Social Security and Medicare remain foundational to the U.S. retirement system, but long-term financing pressures are expected to lead to some eventual changes to funding and benefits.

- Rising federal deficits, the growth of health-care costs, and gaps in structural funding are placing more scrutiny on both programs.

- For high-net-worth individuals, potential policy changes are more likely to be felt through higher taxes, higher premiums, or benefit adjustments.

Concerns about the long-term sustainability of Social Security and Medicare have intensified in recent years. Rising federal deficits, demographic pressures, and growing healthcare costs have all contributed to questions about what these programs will look like in the decades ahead.

Based on current projections, parts of the Social Security system are expected to have insufficient reserves to pay full scheduled benefits beginning in the mid-2030s, if no legislative action is taken. Medicare faces its own long-term funding challenges, as medical costs continue to grow faster than the overall economy. These pressures suggest that while the programs are likely to endure, their structure and financing may change over time.

Although high-net-worth households typically rely less on Social Security for essential retirement income, they are often more exposed to potential policy changes designed to improve program solvency. Understanding the forces shaping the future of Social Security and Medicare is an important part of long-term financial and retirement planning.

Drivers of Future Funding Shortfalls

The funding challenges facing Social Security and Medicare are driven by several long-term structural trends. Together, these forces increase program costs over time while placing pressure on the revenue sources that support them.

Full Retirement Age (FRA)

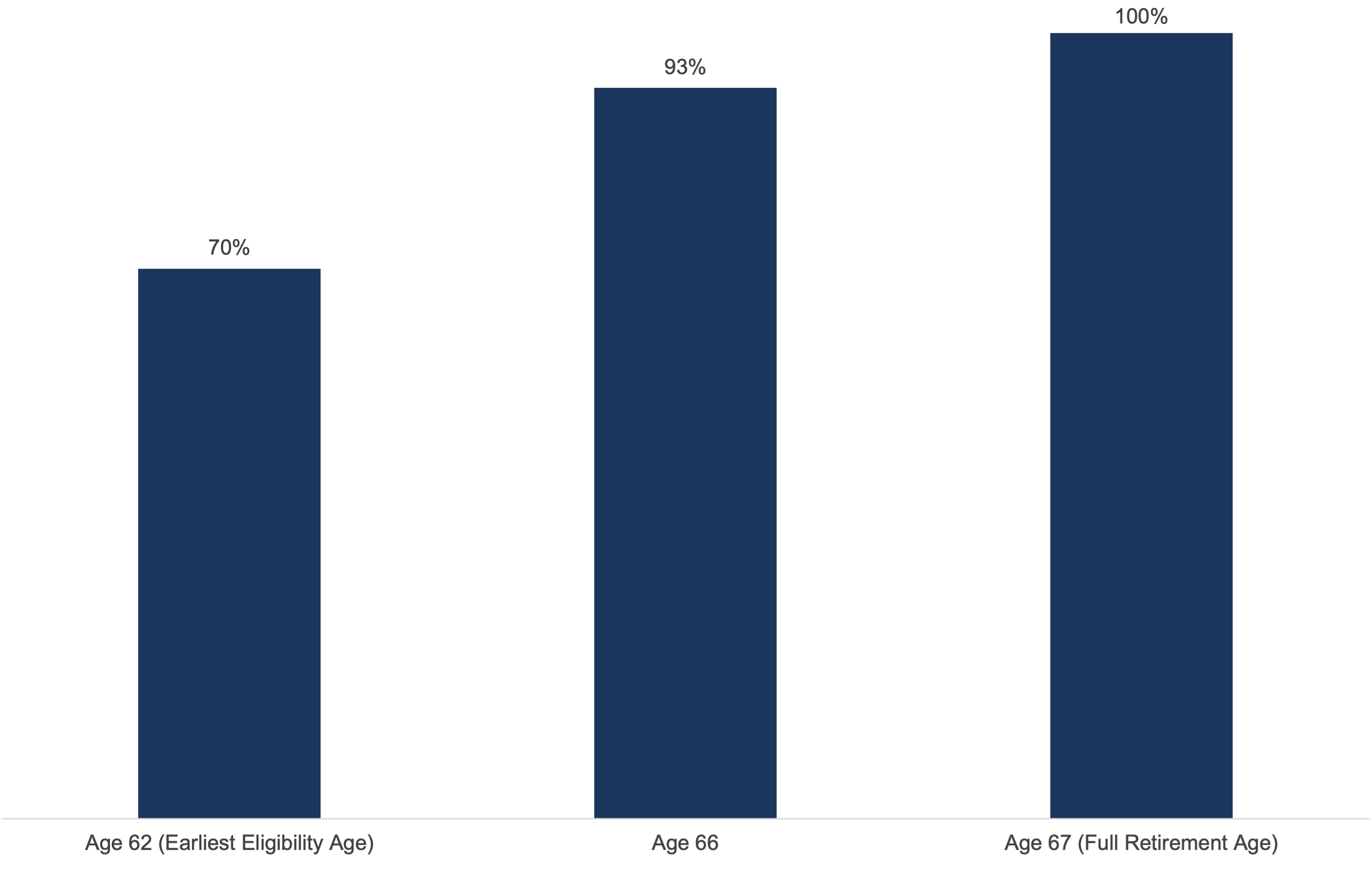

One important structural change is the gradual increase in the full retirement age (FRA), or the age at which individuals are eligible to receive full scheduled benefits. Historically, the FRA was 65, but it has risen incrementally to 67 for individuals born in 1960 or later.1 This change reduces lifetime benefits for many retirees and reflects efforts to align the program with longer life expectancies. It also serves as a reminder that Social Security’s rules have been adjusted before and may continue to evolve as policymakers respond to funding pressures.

Exhibit A: Social Security as a Percentage of Full Retirement Age Benefits (for recipients born after 1960)

Source: Michigan Retirement and Disability Research Center, Fiduciary Trust Company. Data as of December 31, 2025.

Aging Population and Longer Lifespans

As the population ages, the number of beneficiaries receiving Social Security and Medicare benefits continues to grow, while the pace of growth in the working-age population has slowed. At the same time, retirees are living longer, which means benefits are paid out over longer periods than in previous generations.

Healthcare Cost Inflation

Healthcare costs have historically grown faster than overall inflation. Rising prices for hospital care, prescription drugs, and other medical services increase Medicare spending and contribute to higher long-term federal outlays.

Slower Growth in Taxable Wages

On the revenue side, payroll tax growth has not kept pace with benefit obligations. Slower growth in taxable wages limits the inflow of funds supporting Social Security and Medicare, widening the gap between revenues and expenditures.

Taken together, these trends help explain why both programs face long-term funding challenges under current law. While none of these forces alone threatens the immediate operation of Social Security or Medicare, their combined effect increases the likelihood that policymakers will consider adjustments to improve long-term sustainability.

Why Social Security and Medicare Matter

Beyond their importance to individual retirees, Social Security and Medicare play a central role in the broader economy. Nearly every working American contributes to Social Security through payroll taxes, and more than 55 million people currently receive retirement benefits, with millions more relying on disability and survivor benefits.2 Medicare provides health insurance coverage to roughly 69 million Americans, the vast majority of whom are age 65 or older.3 Because of their scale, changes to either program have the potential to influence household spending, healthcare utilization, federal budget dynamics, and overall economic growth.

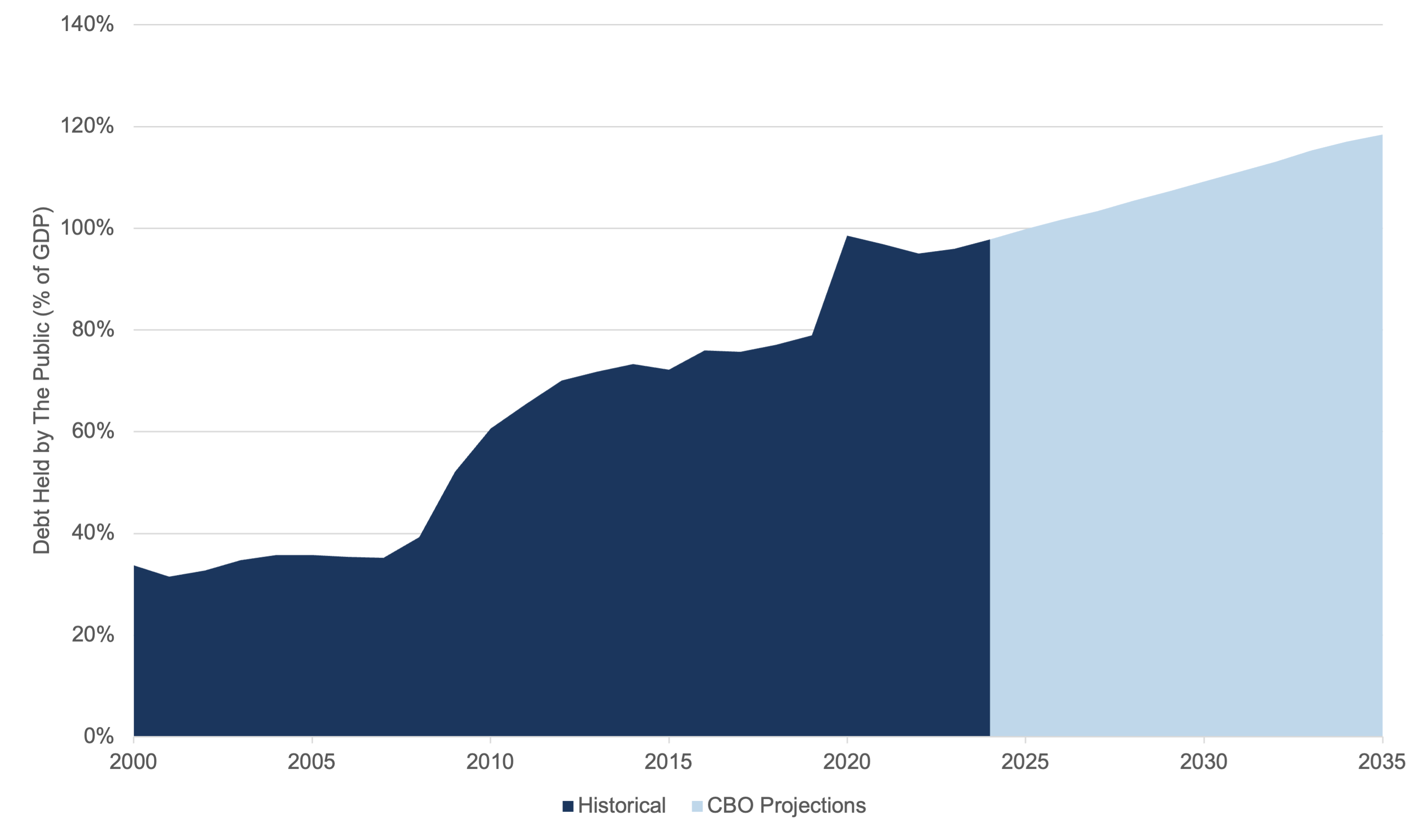

Combined spending on Social Security and federal health-care programs accounted for approximately 10.7% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2024. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), that figure is expected to rise to roughly 14% by 2054, reflecting the growing number of beneficiaries and the higher rate of medical spending relative to the broader economy.4

As Social Security and Medicare consume a larger portion of the federal budget, they play an increasingly important role in shaping the government’s long-term fiscal position and debt. Over the next 30 years, CBO projects that debt held by the public will increase to levels well above historical norms, driven in part by growth in entitlement spending.

For investors, understanding the role Social Security and Medicare play in the federal budget helps provide context for why their long-term financing remains an important consideration in retirement planning conversations.

Exhibit B: US Federal Debt as a Percentage of GDP, 2000-2035F

Source: Congressional Budget Office, Bloomberg, Fiduciary Trust Company. Data as of December 19, 2025.

Social Security’s Outlook

Projections show growing pressure on the system’s reserves over the coming decade:

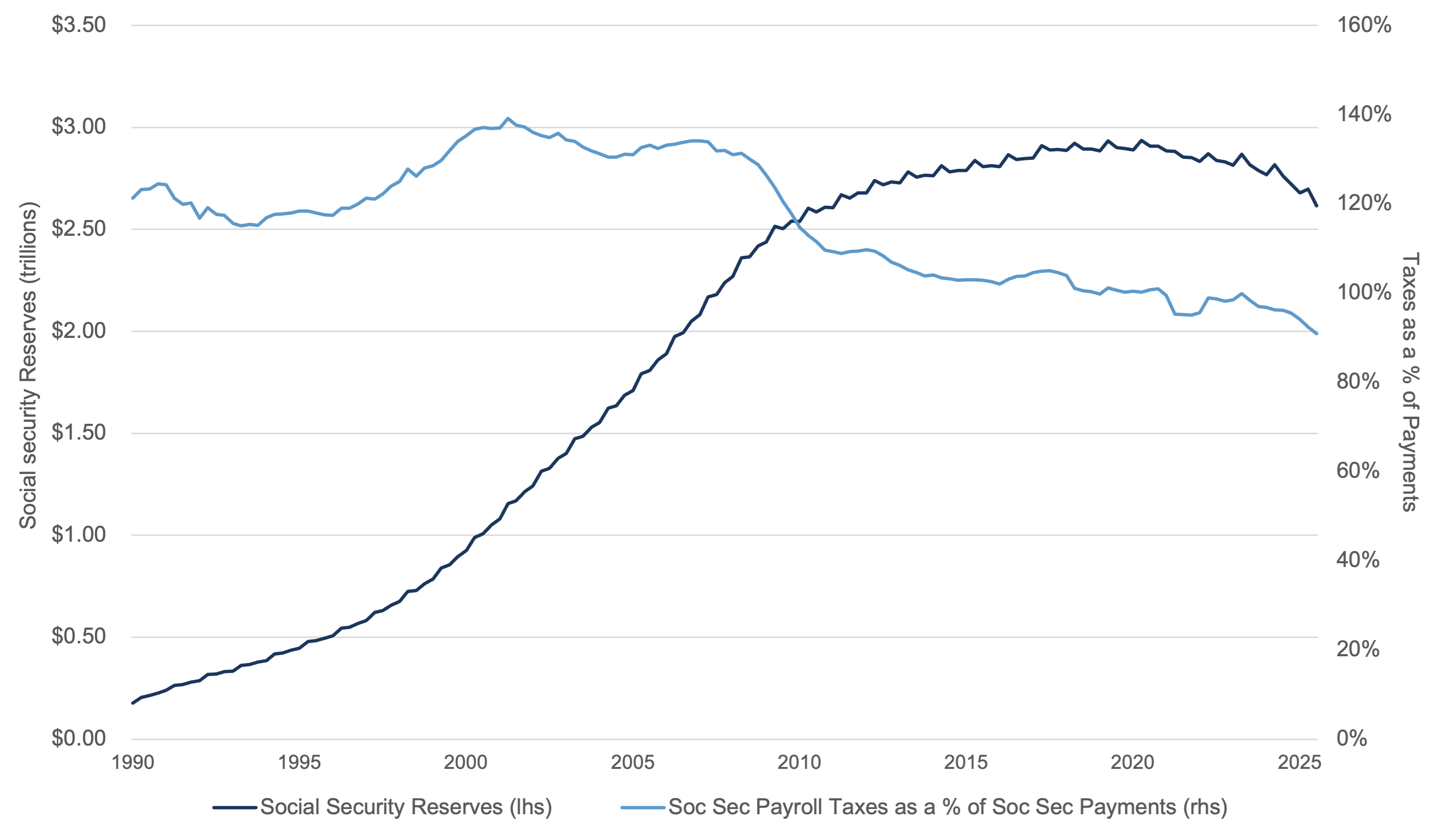

Trust Fund Projections

Social Security is financed primarily through payroll taxes, with excess revenues historically credited to trust fund reserves. According to the report, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund, which pays retirement and survivor benefits, is projected to be depleted in 2033. The combined OASDI trust funds, which include disability benefits, are projected to be depleted by 2035.5

The Actuarial Gap

Over the next 75 years, Social Security is expected to collect less in payroll taxes than it is scheduled to pay out in benefits. The size of this gap is estimated to be about 3.5% of taxable wages, or roughly 1.2% of the overall U.S. economy.6

Exhibit C: Social Security Reserves and Payroll Tax Funding

Source: Social Security Administration, Fiduciary Trust Company. Data as of December 19, 2025.

Medicare’s Outlook

Medicare faces its own long-term funding challenges, though its financial structure differs from that of Social Security. The program is financed through two separate trust funds, each with distinct funding dynamics and risks.

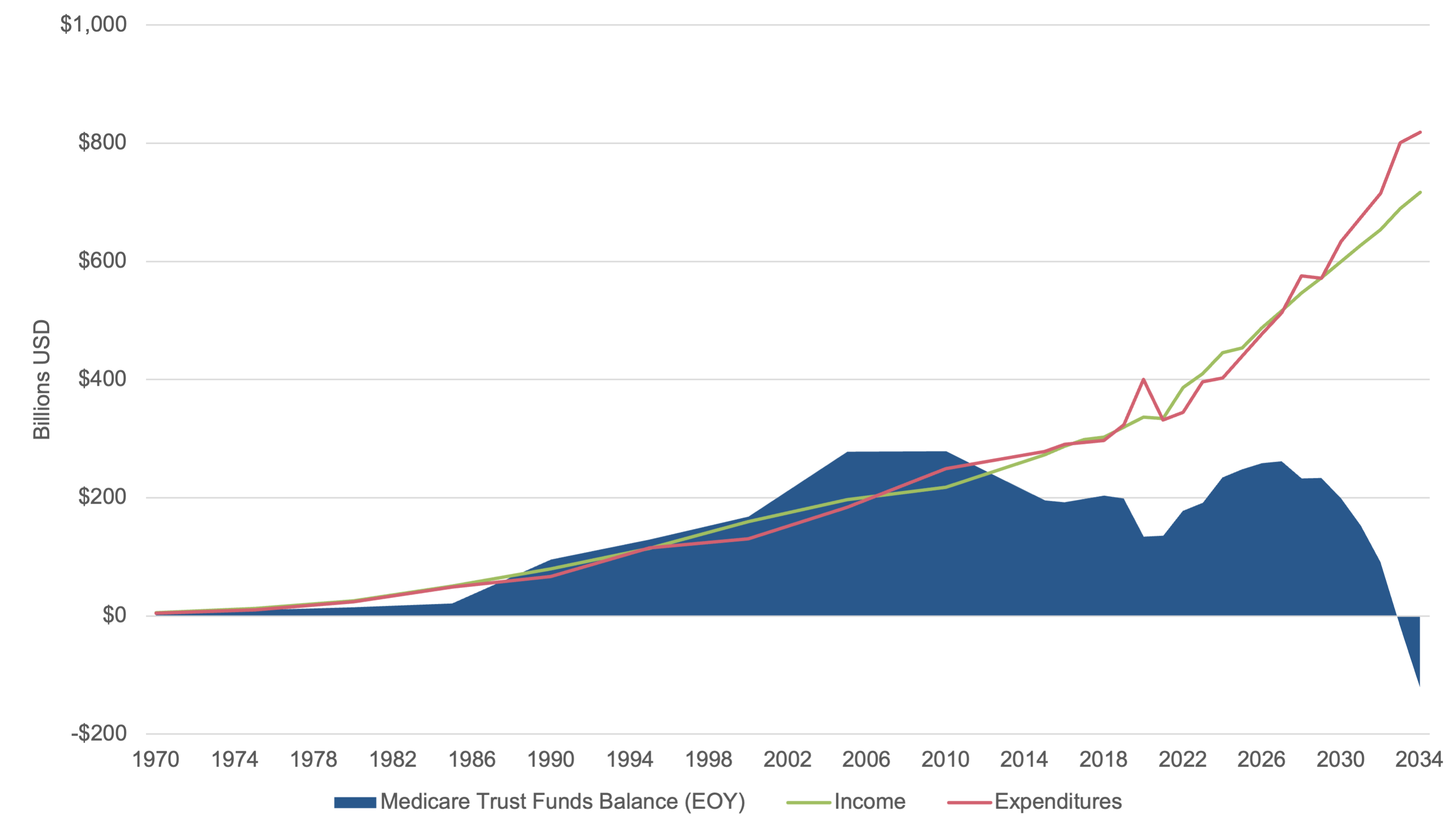

Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund

Medicare Part A, which covers hospital care, skilled nursing facilities, hospice services, and some home health care, is financed primarily through payroll taxes and relies on the Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund. According to the Medicare Trustees, the HI trust fund is projected to be depleted in 2033, as program spending continues to outpace dedicated revenue sources.7

Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI)

Other components of Medicare, including Parts B and D, are financed differently. These Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) programs are funded through a combination of beneficiary premiums and general federal revenues, which are adjusted annually to cover projected costs. This structure ensures ongoing solvency, but contributes to rising federal spending and higher premiums for beneficiaries.

Healthcare Costs and Budget Pressures

Medical costs have continued to grow faster than overall inflation, placing upward pressure on Medicare spending and the federal budget. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, restoring long-term Medicare solvency would require either a meaningful increase in payroll tax revenues or a reduction in program spending.8

Exhibit D: Medicare Funding

Source: 2025 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, Fiduciary Trust Company. 2025-2034 data is based on projections.

As healthcare costs rise, Medicare’s role in shaping federal spending – and potential policy responses – will remain an important consideration for long-term retirement planning.

Potential Impact on Future Payments and Coverage

If no legislative fixes are enacted, and if Social Security’s retirement trust fund is threatened with insolvency, scheduled benefits would have to be automatically reduced once reserves are depleted. In that extreme scenario, recipients could be looking at an across-the-board cut of roughly 24%.9

For retirees, this could translate into a meaningful reduction in income. Estimates suggest that a typical couple retiring after insolvency could face an annual benefit reduction of approximately $18,000.10

Looking ahead, policymakers have several broad tools available to slow the depletion of Social Security’s trust funds. Commonly discussed options, which would impact income and benefit expectations, include increasing payroll tax revenues, adjusting benefit formulas, gradually raising the full retirement age, or modifying cost-of-living adjustments. Any reforms would likely be phased in over time rather than implemented abruptly.

On the Medicare front, potential responses include higher income-related premiums, changes to coverage or cost-sharing, adjustments to provider payments, or increases in dedicated funding sources. As healthcare costs continue to rise, these issues remain central to Medicare’s long-term outlook.

For high-net-worth individuals, the effects of future reforms may be more pronounced, as higher-income households already pay elevated Medicare premiums and are more likely to have a greater share of Social Security benefits subject to taxation. Overall, these dynamics suggest that while Social Security and Medicare are likely to endure, future benefits and costs may differ from those seen today.

Conclusion

Social Security and Medicare are not at risk of disappearing, but their long-term trajectories suggest that change is likely coming. Rising healthcare costs, demographic pressures, and growing federal budget constraints point toward gradual adjustments rather than abrupt disruption.

Understanding these dynamics is important. While the exact form of future reforms remains uncertain, changes are more likely to affect higher-income households through taxes, premiums, or benefit formulas. Staying informed about the broader fiscal backdrop can help frame more resilient, long-term planning considerations.

Fiduciary Trust Company continues to monitor developments in Social Security, Medicare, and federal fiscal policy. If you would like to explore how different scenarios may affect your retirement outlook, please reach out to your investment officer or Sid Queler at squeler@fiduciary-trust.com to discuss how Fiduciary’s wealth planning team can help.