Christie’s Americas Chairman Emeritus Stephen S. Lash discusses current trends and drivers of demand in the world of art, as well as the best way for budding enthusiasts to start collections.

Whether motivated by a passion for a particular category of art, a desire to invest in an “alternative” asset class, or a need to understand the importance of inherited pieces, many of our clients are interested in art. This curiosity ranges from those who are experienced collectors to those who are in the early stages of building collections.

Given the attention art is attracting, we connected with a global expert, Stephen S. Lash, Christie’s Americas Chairman Emeritus, to get his unique perspective. The following is an edited conversation in which Stephen offers his views on art and which areas are attracting the greatest interest.

Key Trends in Art

FTC: In building a collection, how should a collector balance what he or she enjoys most with what’s likely to deliver the best investment returns?

SL: This is a really important question. In thinking about this, it leads me to conclude that collectors often make successful investors. However, that is not their intention when they are first starting out and, for many, their initial success may be more attributable to luck. The reverse, though, simply does not apply. Investors do not make good collectors. Investors – pure investors – rarely, if ever, make wise collecting decisions, unless they’re privy to the best possible advice.

There are two real ingredients in picking art that will appreciate in value. The first is quality – you cannot compromise on the subject of quality. The second ingredient is freshness. The art market does not like to see an object come back on the market too soon.

So if you have a quality piece of work that has not been seen in the past 30 to 50 years, or ever, those are the pieces that will generate the most excitement. There are examples, for instance, of major pieces of twentieth-century art that were bought early in the twentieth century by major collectors. These artworks may have remained in a particular family for an extended period of time. When these paintings come up for sale again they are very sought after, because they take the market by surprise. From the perspective of the collector, they represent a “now or never” opportunity.

FTC: What types of art are in greatest demand today and what is driving interest in these areas?

SL: Right now, the taste for Post-War and Contemporary art is particularly high. There are new collectors who will enter the art market and immediately gravitate to Post-War and Contemporary art. They tend to ignore a lot of the other areas that are probably considered more esoteric.

In general, I think there’s something counter-intuitive about the art business. In most economies, a shortage of supply triggers demand. In our business, the presence of supply sustains demand. And as soon as supply begins to dry up and it becomes less easy to collect, the demand will often deteriorate. It’s an observation, but I think people want the gratification of being able to find something when they’re ready to buy it. You saw this dynamic play out with Old Master paintings, eighteenth-century porcelain, and Ming Dynasty porcelain.

Example: Post-War Contemporary

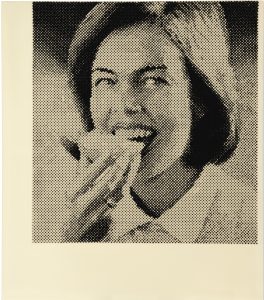

Sigmar Polke (1941-2010)

Sigmar Polke (1941-2010)

Frau mit Butterbot, 1964

Sold for $17M in May 2017 at Christie’s in New York

Artwork courtesy of Christie’s Images LTD 2017

FTC: So is it fair to say that there are fewer Old Master pieces because there are actually fewer of them or is it because people have them in their collections and don’t want to sell them?

SL: There are fewer Old Master pieces because they are no longer being produced and they’re in short supply. The great masterpieces – and I’ll come back to that word – have been bought up and are locked away either in private collections or in museums, so there seems to be less opportunity for collectors.

That said, I think it’s a neglected area. The quality of art in this category is high – or can be high – and the prices are much more reasonable than they are for many Post-War and Contemporary art pieces. These are also artists who have stood the test of time. They were painting 300 or 400 years ago and are established, whereas many contemporary artists may drop by the wayside.

Example: Old Master

Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640)

Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640)

Lot and His Daughters, circa 1613-1614

Sold for 45M Euros in July 2016 at Christie’s in London

Artwork courtesy of Christie’s Images LTD 2017

FTC: If you look over the last 20 or 30 years, have Old Masters held flat in value while Contemporary pieces have taken off?

SL: Old Masters were on the rise well into the 1980s and then demand began to taper off. Today, Old Masters are less expensive than they were, say, 10 or 15 years ago.

FTC: What factors do you see driving demand for various types of art over the next 10 or 15 years?

SL: I said I would come back to the word “masterpieces.” In addition to the category of Post-War and Contemporary art, there is another category, which is quite unrelated in many respects. That would be the category of Masterpieces. There are buyers today who are only looking at Masterpieces.

That’s a very important development and reflects one of the trends we’re seeing, generally, as economic growth can often serve as a catalyst for an influx of new collectors. Today, the growing presence of Chinese buyers in the market has had a tremendous influence on the market at large and buyers from Asia now account for about 30% of annual art purchases worldwide. The growth, even over the last five years, has been significant.

In terms of how this has impacted the market, Asians, particularly Chinese collectors, began buying back their heritage, if you will, about five years ago. They were initially combing places like the United States and Great Britain for works of art that might have been exported decades ago, or even a century ago. Many of the collectors were focusing on these pieces and bringing them back to China. Gradually, the interest broadened to include non-Asian work, and initially many collectors gravitated to Impressionist and Modern paintings. Now it has morphed into a real appetite for Masterpieces, at the very highest level.

Some of this is investment driven; collectors will often take comfort in owning hard assets. The conventional wisdom is that if the quality is good enough, the art will hold its value and there’s some truth to that.

I think there is also a degree to which collectors appreciate the social cachet that comes with owning high-profile works of art. This applies, in particular, to the prestige that accompanies collecting many Post-War and Contemporary art pieces. These are works of art that are most often instantly recognizable. So, if you have an Andy Warhol, a Jasper Johns, a [Willem] de Kooning, or a Jackson Pollock over your fireplace, the colleagues you invite home for dinner will likely recognize these pieces.

Building a Collection

FTC: For someone interested in building a collection, how would you advise them to get started?

SL: The best way is simply to start looking. Go to your local museums; see what you like. Talk to the people in the museums; ask to meet the curators. Go to the dealers who specialize in the fields that interest you. You can find out who they are through local channels or through the museum curators. And don’t forget that auction houses host public and virtual exhibitions in advance of every auction; these are free, open to the public, and specialists are on hand to discuss both the aesthetic and commercial aspects of all of the featured works. In general, just look, look, look and train your eye.

FTC: What are some common mistakes that beginning collectors make?

SL: Novice collectors often make the mistake of buying without good advice. Some people will say, “Buy what you like, and it’s fine.” But it’s not fine, because there are people in the art world, like every other industry, who will overcharge for things and take advantage of people’s inexperience.

There are also huge risks to buying without knowledge. For instance, something may look like it’s in good condition but it’s not. It could be a piece of furniture or a piece of porcelain that has been very discreetly repaired and that obviously damages the value.

Also, buying something with clouded provenance or history is another area where novice collectors can run into trouble. Right now, at Christie’s, we have an entire restitution department that studies the history of the objects we offer for sale. This came out of the fact that so many pieces were looted by the Nazis before and during World War II. If you’re an American and you end up owning a piece of looted art, you’re obliged to return it if you become aware that it was stolen. Of course, you theoretically have recourse to go back to the person who sold it to you, and they have recourse to go further down the chain, but that is a complicated process and collectors would be well advised to avoid these situations.

For many of our best clients, the thrill of owning something is worth the responsibility that goes with that stewardship. In fact, the word “stewardship” is really the operative term. If you’re not prepared for that responsibility, then this is probably not an activity you should get engaged in.

Disposition of a Collection

FTC: When a collector is interested in selling part or all of their collection, what are the best ways to maximize the value they receive?

SL: The key consideration is, “What is the best way to sell this particular category of object or group of objects?” I’m very pro-auction because I think it’s very efficient and the reach today is truly global. But auction is not necessarily ideal for every object. Again, if you’re talking about a relatively recent painting by a young artist, the best thing to do would be to go back to that dealer.

We live in a competitive world; you might as well take advantage of the resources that are out there. Don’t just talk to one auction house; talk to several. Also, make sure the confidentiality of what you’re discussing is acknowledged, perhaps in a formal way. Not all auction houses maintain the same high standards for client confidentiality. You’ve got to be very careful about that.

FTC: Are there other things you can do to make a piece more valuable?

SL: You have to educate yourself. I would suggest you talk to primary auctioneers or the secondary auctioneers if that seems appropriate—the dealers and the museums. One of the gratifying things about this business is how willing the specialists are to share their knowledge. The means of maximizing the value of one object may be very different from the way you would want to maximize the value of other objects, so it pays to seek out the relevant expertise.

FTC: With the transition of art in an estate, are there some often overlooked factors or options that a collector should consider?

SL: When I said to be very careful in thinking about art as an investment, that comment was really directed toward the new buyer—the person with a pool of cash who wants to do something with it and could buy either stocks, real estate, or art.

On the other hand, there is a whole different category, which is the owners. We’ll also refer to these people as the “havers,” who bought or inherited pieces years ago that have appreciated dramatically, and these pieces may account for a significant portion of their net worth. This category of collector is really obliged to think of art as an asset class because the value of their collection may so far outdistance the value of everything else they own. In these cases, it becomes a major estate-planning issue.

I would really encourage these collectors to seek up-to-date appraisals. It’s often the case that people do not know the value of their possessions. And appraisals are easy to get from local providers or from the auction houses, themselves. What I would be very careful about is the use of generalist appraisers, exclusively, however. This is a very specialized world. The fact that a painting by a particular artist has sold for a record price does not mean the next painting by the same artist will also attract a record price. Picassos are not interchangeable. Mondrians are not interchangeable. So it really behooves investors to make the effort to know the real value of their collections.

Clearly, there are a number of important considerations when collecting art, as discussed in this interview. Art can provide lifelong enjoyment, and also deliver pleasure and potentially monetary value for future generations. Read the related article, “Gifting with Knowledge,” for our insights on planning for art transition in an estate.